The Outbreak of War

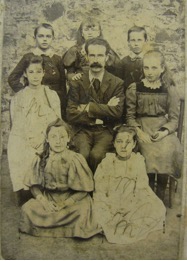

The year that the war started began with tragedy for Bishopsteignton School’s Headteacher, his wife, who also taught at the school, and their family. His stoical entries in the School Logbook on April 1st and April 7th 1914 indicate the depth of their loss: “Mrs Wallis away due to the sudden death of our little boy” and six days later: “No school today owing to our little boy’s funeral.”

At the beginning of World War One the school in Bishopsteignton was housed in what is now the Community Centre at the heart of the village. Bishopsteignton School was then a Church of England school with Mr Clifford Wallis as Headteacher. In November 1914 the school had a population of around 140 to 150 children.

At that time, Luton had it own school with Miss White as Headmistress, overseeing the education of approximately 40 children. Both schools were governed by a committee of managers who met once or twice a term.

In Bishopsteignton School the children were taught in two rooms with the infants in one room, taught by Mrs Wallis, and a mixed class in the other room, taught by Miss S. Wallis and Mr Wallis. So the school was very much a family affair with the Headteacher’s wife and daughter making up the teaching staff.

Mr Clifford Binman Wallis, headteacher at Bishopsteignton Primary School, with some of the schoolchildren

Patriotic work by the children

The school was largely unaffected by the outbreak of war. In 1914 the school routine continued as normal including regular visits by the School Attendance officer, the Vicar, the Medical Officer and the Dentist. In April 1914 comments were made about the overcrowded state of the school. “The crowded room makes working very difficult.”

Medical inspections were very regular and there were fairly frequent outbreaks of scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough and measles. In the school logbook the first reference to the war was on October 30th 1914;

“The girls here have been very busy lately, knitting socks for our soldiers at the front. They have given up most of the recreation time and as the result 37 pairs of socks were forwarded to the Queen by Mrs Wallis today.”

The children of Bishopsteignton Primary School knitting socks for soldiers in WW1

On the fourth of November the logbook recorded; “some children of Belgian refugees attended today, no names were entered as the language is not yet understood by anyone in the village. ”

So the school carried on as normal in 1914 and in December of that year following an inspection, the report by the Diocesan Inspector classed the school as “excellent .”

In May 1915 it is highly probable that the war was the focus of the Vicar’s address to the children for the Empire day celebrations “and the patriotic tone was reinforced when the school band played the national anthem.”

The Bishopsteignton Primary School Band WW1

After nearly a year of war the impact was beginning to be felt and one result was the closure of the school in June 1915 for two weeks so that the older children were able to help to bring in the harvest as there was a shortage of labour.

Recruitment was an ongoing issue during the First World War and the school children were given the opportunity to meet soldiers of the recruiting detachment in September 1915.

The Overseas Club

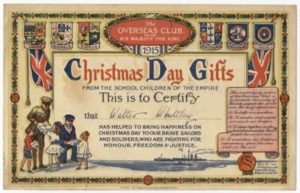

In December the children collected 12 shillings for the Overseas Club and Overseas Certificates were given to a number of children.

Overseas Certificate given to children of Bishopsteignton Primary School during WW1

The Overseas Club

Imagine spending Christmas day without a tree or turkey, sitting in a muddy trench with strangers. Christmas was a particularly hard time for servicemen in the First World War, when they began to feel especially homesick and their morale suffered. A charity called the Overseas Club decided to supply men on the front line with Christmas gifts to raise their spirits.

In 1915, the charity sent out an appeal to schoolchildren, asking them to raise money so that gift boxes could be purchased and sent to servicemen. Sir Edward Ward, who was in charge of the Overseas Club, wrote to children, asking them to imagine ‘how unhappy [the soldiers] must be…when they have to stand hour after hour, in the trenches, often deep in water, with shells bursting all around.’

The money raised was used by the charity to fill the boxes with small, useful presents to make soldiers’ lives more comfortable, such as socks, chocolates and cigarettes (at the time people did not realise that smoking caused health problems).

Children who raised over a certain amount of money received a certificate praising their efforts. Walter Whiteley, a young boy from Sheffield, was sent an Overseas Club certificate for his fundraising work in 1915 (pictured above). The certificate shows two children passing presents to a soldier and a naval officer. On the bottom left is a seal of approval and the aims of the Overseas Club are written out, including: ‘to help one another’ and to ‘draw together in the bond of comradeship British people the world over’.

Empire Day 1916

Heavy snow in February 1916 meant that attendance was very poor but despite this cooking classes were still held In Teignmouth for the girls.

On 24 May 1916 the children assembled in the playground to commemorate Empire Day and saluted the flag. The Vicar addressed the children and “patriotic songs were sung accompanied by the school band, which was gratefully appreciated by a large gathering. A holiday was given and the children paraded headed by the band. The Collection for the overseas club amounted to thirteen shillings”.

The regular meetings of the School Managers continued but in November 1916 their attention was focused on their responsibilities at Luton School when they received notice that the School House had burnt down. Fortunately, the main school building was saved but the school had to be closed for ten days for repairs. This meant that the Headmistress had no accommodation, a situation which eventually caused her to leave. This situation and falling pupil numbers threatened the school with closure. This uncertainty about the future resulted in a series of short term temporary Headteachers.

Pupils’ Good Work

Bishopsteignton School continued to support the war effort and in July a sale of work and an exhibition of needlework was held in the school. “It was in aid of the school wool fund for knitting socks for the soldiers and sailors and all of the articles were made by the children. Lady Cable of Lindridge attended and opened the sale”.

Luton School also worked to support the war effort. The School Logbook described how, in July 1914, the school “assembled half an hour earlier to enable older children to leave at three thirty to pick sphagnum moss on the common for the Red Cross for wounded soldiers and sailors”.

Millions of wound dressings made from Sphagnum, or ‘bog moss’, were used during World War I (1914-1918). Dried Sphagnum can absorb up to twenty times its own volume of liquids, such as blood, pus, or antiseptic solution, and promotes antisepsis. Sphagnum was thus superior to inert cotton wool dressings (pure cellulose), the raw material for which was expensive and increasingly being commandeered for the manufacture of explosives.

In 1917 the effect of conscription was increasingly being felt by the village. Written in the School Logbook was the comment that the school was “having great difficulty in obtaining fuel for the fires. The village carrier has been ‘called up’.’

1917, Rationing and Conkers

Later, in 1917, there must have been great excitement when two bandsman of the 10th Londoners stationed in Teignmouth visited and played with the school band. The impact of the war was being increasingly felt. The Vicar visited the school “to leave notices concerning voluntary rationing”.

Empire day was celebrated with a parade and in the summer boys were required to help with the harvest, teachers attended drill classes in Teignmouth and the girls carried on knitting of socks for the soldiers. However the children’s education continued more or less as normal and the Diocesan report in November awarded the school “the highest mark”.

In March 1918, the school logbook records that; “700 weight of chestnuts were dispatched to the Minister of Munitions. These were collected during the autumn by the children”.

When Britain’s war effort was threatened by a shortage of shells, the government exhorted schoolchildren across the country to go on the hunt for horse chestnuts.

In the autumn of 1917, a notice appeared on the walls of classrooms and scout huts across Britain: “Groups of scholars and boy scouts are being organised to collect conkers… This collection is invaluable war work and is very urgent. Please encourage it.”

It was never explained to schoolchildren exactly how conkers could help the war effort. Nor did they care. They were more interested in the War Office’s bounty of 7s 6d (37.5p) for every hundred weight they handed in, and for weeks they scoured woods and lanes for the shiny brown objects they usually destroyed in the playground game.

The children’s efforts were so successful that they collected more conkers than there were trains to transport them, and piles were seen rotting at railway stations. But a total of 3,000 tonnes of conkers did reach their destination – the Synthetic Products Company at King’s Lynn – where they were used to make acetone, a vital component of the smokeless propellant for shells and bullets known as cordite.

Death of Clifford Wallis

The logbook entry for May 3, 1918 brings home the reality of war and a second tragedy for the Wallis family; “school closed without notice owing to the reception of the news suddenly that the eldest son of the Headteacher, Private Clifford Edward Wallace, had been killed in action in France”.

42625 Private Clifford Edward Wallis of the 2nd Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Son of Clifford B. and Eleanor Ann Wallis, of School House, Bishopsteignton. Born in Bishopsteignton in the March Quarter of 1896. Died 25 April 1918

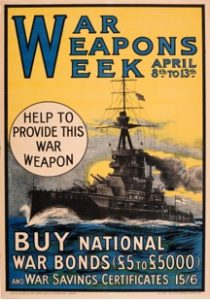

War Weapons Week

July 15, 1918 was War Weapons Week, which gave the impetus to raise money for the school branch of the War Savings Association.

Poster to promote War Weapons Week 1918

In 1916 a National Savings Committee had been established with the small investor as its principal target. The associations were formed in connection with social groups, such as churches schools and workplaces.

Food rationing was introduced in 1918 and a committee was set up to look at the ways of utilising any available natural resource. Throughout the country, rural schools were instructed “to employ their children in gathering blackberries during school hours” for the Government jam making scheme.

1918 and the End of WW1

The Bishopsteignton School Logbook for October 1, 1918 records that; “no school this afternoon, the children being given time for blackberrying. In the evening teachers received the berries and weighed them. This initial amount was over 200 lb in weight”.

The collecting continued for the rest of the week and over a thousand pounds in weight was collected for which the children were paid at a rate of three pence per pound.

Fundraising became an increasingly important aspect of school life and more effort by the children, especially the school band who paraded around the village, raised £10 for the Red Cross.

The final days of the War passed quietly in Bishopsteignton School as it was closed from 21st October for over two weeks due to an influenza outbreak.

The school was still closed on Armistice Day although the children who were well enough assembled and headed by the school band, paraded round the village. Flags were displayed from nearly every house and amidst a great enthusiasm stoppages were made and the National Anthem sung.

Luton School finally closed on December 13th 1919