Context and Background

The ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign was vital to help keep the country fed well and healthy during both of the World Wars and also during the years after. This is the story of the campaign and its relevance on a local level.

The ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign was an extremely successful marketing initiative which encouraged many members of the public to grow their own produce hence reducing Britain’s reliance on imports.

The importance of ‘Dig for Victory’ was not only to provide much vital food for civilians but it also:

· Freed up space on ships to carry weapons, munitions and raw materials that were vital to keep the armed forces supplied.

· Freed up space so masses of troops, who were vitally needed, could be transported to Europe and Asia.

· Prevented the country from importing food that cost money especially as by this time the country’s financial reserves were very depleted. Therefore we basically could not afford to import food when we could grow it locally.

During the pre-war years of the 1930s around 75% of Britain’s food was imported through shipping. Without ‘Dig for Victory’ it is very possible that the enemy’s U-boats, which attacked the Merchant Fleet in numerous and dreadful raids, could have resulted in starving Britain’s population and thus forcing surrender.

The ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign was initiated by the British Ministry of Agriculture in 1939 and according to the War Cabinet’s records, by 1941 food imports had been reduced by nearly half. This campaign was extensive, educating the public via leaflets and guides and many short films shown at the cinemas to encourage and help them to start planting on any land available using the slogan ‘Spades not Ships!’ Open spaces were transformed into allotments including; home gardens, parks, factory courtyards and even the gardens of the Tower of London and Buckingham Palace. It is estimated by War Cabinet records that by 1942 half of the public were part of the nation’s ‘Garden Front’.

Such was the popularity of this propaganda campaign which was not only led by using cartoon characters such as Captain Carrot and Potato Pete but also saw 3.5 million people listening to Cecil Henry Middleton, Britain’s first celebrity gardener, on the Home Service giving much needed advice and tips on growing and Marguerite Patten giving cooking tips, that it not only educated the public but kept spirits and morale high during desperate times.

‘Householders were told they were on the ‘Kitchen Front’ and that they had a duty to use foods to their greatest advantage.’ 1

The Royal Horticultural Society also played a vital role for ‘Dig for Victory’ in both WWI and WWII and by the end of WWII they estimate that there were nearly 1.4 million allotments in Britain, producing 1.3 million harvests.

Government essentially needed to increase food production and recover pasture lands and any other unused lands for growing, and with the majority of men going away to war, women stepped into ‘men’s shoes’ within many industries including agriculture.

Land Girls

The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was first formed during WWI. This was a time when men undertook the majority of work on the farms; however, when they were ‘called up’ to fight for their country there became a massive shortage of farm workers.

The WLA was again reformed on 1 June 1939 shortly before the start of WWII by Lady Trudie Denman who was a leading figure in the Women’s Institute movement, had an interest in rural affairs and was also responsible for creating the WLA during WWI. If war broke out men working on farms would again be ‘called up’ fearing a shortage of labour, resulting in a shortage of food production. After discussions Lady Denman finally persuaded the Ministry of Agriculture to advertise the work of the WLA to farmers across the country to increase workers in food production. Lady Denman’s home in Sussex became the WLA headquarters and each district had its own WLA representative to ensure that the Land Girls were treated well and worked effectively. To ensure duties were successfully performed at an allocated farm each WLA girl was required to attend a month’s training.

‘The land army fights in the fields. It is in the fields of Britain that the most critical battle of the present war may well be fought and won’. (Lady Denman, Director of the Women’s Land Army) 2

The above quote encapsulates how important the Land Girls were during WWII and the reality that they had an opportunity to do ‘their bit’ for their country and hence enrol in the WLA. With victory in 1945 the Land Army was disbanded in 1950.

Initially the Ministry of Agriculture requested women to volunteer for the WLA by enrolling at a local Women’s Land Army headquarters, undertaking a medical test and then attending an interview; but in 1941 the government passed the National Service Act, conscripting women into the armed forces or vital war work. Single women between the age 20-30 and widows without children were called up first; however, this still could not fill the short fall of vacancies needed to replace the men and the age group was increased later on to those between 19-43. Women began to do the jobs that men had previously done before, mechanics, drivers, air raid wardens, working in factories and also supporting food production and resources for the country. The women could choose either to join the armed forces, work in industries or work in farming. By 1943 there were nearly 80,000 women working in the land army, these girls hence became nicknamed the ‘Land Girls’.

The Land Girls worked long and hard hours (minimum of 48-50 hours a week), ploughing, harvesting, rat catching, general farm maintenance, reclaiming land, or working in the timber corps in all sorts of weather. They came from many backgrounds, from many cities and towns and some were very homesick, they were also resented by some farmers. Their living conditions were very basic and sometimes very lonely, living at farms where they worked or at hostels.

Pay was minimum and paid by the farmer who employed them, i.e. 28 shillings (s) per week and then 14s deducted for board and lodging, that’s if they got paid properly. Initially there were no holidays, paid or unpaid and after 6 months of work they received a free pass. In 1943 conditions improved, with an increased minimum wage and the introduction of a one week holiday when the ‘Land Girls Charter’ was introduced. Their uniform consisted of a green jumper, brown breeches or dungarees, brown felt hat and a khaki overcoat. The WLA badge consisted of a wheat sheaf which became the symbol of their hard work. Although initial training was given many learnt on the job and ‘The Land Girl’ official magazine became available (although not to everyone), to provide much needed information and portray a sense of not being alone; for example, it tackled typical issues they would face and gave practical advice on how to deal with them. It also aimed to unite all the Land Girls across the country together.

The Land Girls Official Song was:

‘Back to the land, we must all lend a hand

To the farms and the fields we must go.

There’s a job to be done

Though we can’t fire a gun

We can still do our bit with a hoe.

When your muscles are strong

You will soon get along

And you’ll think that the country life’s grand;

We’re all needed now,

We must speed with the plough,

So come with us – back to the land.’ 3

Land Girls were very committed to the cause and became valued members of the new communities they worked and lived in; and when some of them eventually returned home they had formed lifelong friendships with the farmers and fellow Land Girls.

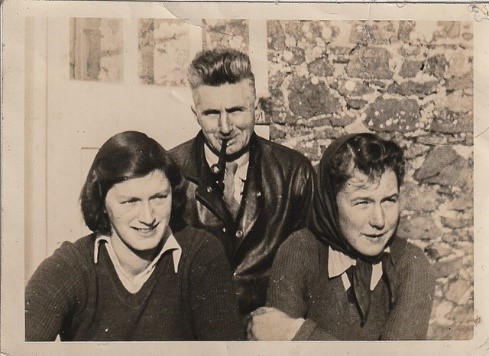

The following comment is provided by Mr Paul Thomas (in Australia) whose mum, Jeanne Thomas, (nee Phillips) was one of the Bishopsteignton Land Girls, who was based at Murley Grange.

“Mum always wore a head scarf at work and as you know continued to do so for outdoor activities. She found hats were rather uncomfortable to wear at times. Mum said that they grew cauliflowers and were paid very little for them, considering the work that was put into growing them. She also said about it being painful on the hands in the winter when gathering the vegetables during wet cold weather. The vegetables used to be collected early morning and taken to London to be sold the same day. Her land army socks made good Christmas stockings!” 4

Jeanne Thomas, nee Phillips

The above photo was taken at Murley Grange, Bishopsteignton, Devon 1944. The people on the photo were Betty Davey, Harry Burgoyne-Head Gardener and Jeanne Thomas, nee Phillips, (pictured on the right).

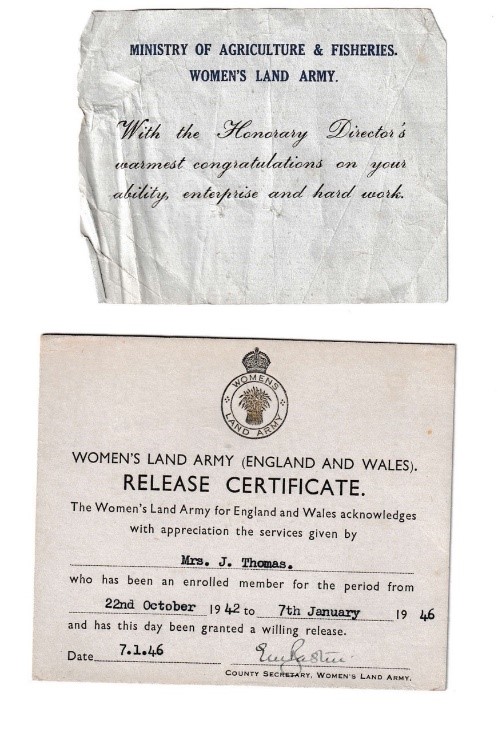

Jeanne Thomas, nee Phillips Land Girl service record.

How was Devon Involved?

Devon provided a lot of the much needed food for the county and many of the Land Girls and WLA worked on the Devonshire farms because of their agriculture background. Therefore Devon helped to change the way that women were viewed from ‘stay at home wives’, to women who were determined to and successfully manage the many jobs effectively in agricultural.

Rationing

Again due to the attacks on shipping by U-boats, rationing was initiated in early 1940 after the war started, to ensure and regulate that available food and commodities were fairly shared and available at affordable prices for everyone. During National Registration Day, September 1939, every household were required to register everyone living in their home. With this information the government issued everyone with an identity card and ration book, which included coupons for the rationed commodities that could be bought weekly. Although items still needed to be paid for, this system ensured a fair share of use and prevented hoarding and extortionate pricing of items.

With the introduction of unfamiliar foods, for example, dried eggs and spam, The Ministry of Food (responsible for rationing) ran an educational campaign, by issuing monthly guides to inform the public on how to make the most of their rations, how to avoid waste, give them ideas on how to make mealtimes more interesting and what to do every month on the allotment.

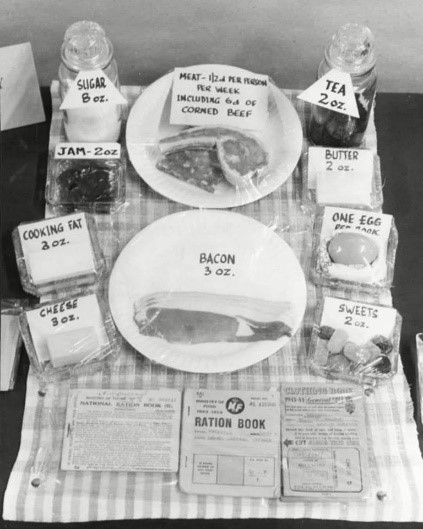

Ration books were handed out to all individuals, who then were required to register at certain retailers. When purchases were made they were ‘stamped’ in the book by the shopkeeper. Certain groups of people, i.e. miners, the WLA and members of the forces, were allowed additional rations of food. Petrol was the first commodity to be rationed, followed by butter, sugar and bacon and then the majority of food with the exception of fruit and vegetables, with clothing and furniture to complete commodity rationing. The government encouraged everyone to increase their intake of vegetables by the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign.

A weekly ration for one person included: one fresh egg, 2 oz butter, 2oz tea, 2 oz cheese, 8oz sugar, 4oz bacon and ham, 4oz margarine, meat 1 shilling, milk 3 pints, preserves 1lb every 2 months, sweets 12oz every 4 weeks.

Weekly Rations

Why not try and cook this WWII pudding using the rations at the time?

Ration Pudding

Clothing rationing began in 1941 and finished in 1949 due to the shortage of materials available to make clothes for civilians, as all available material was urgently required to make parachutes, uniforms etc. The coupon system allowed one completely new set of clothes annually and different coloured coupons ensured buying was staggered across the rationing time scale. Initially 60 coupons annually were available, however later on in the war this was reduced to 48. Children were allowed an extra 10 coupons for growing spurts. The government called on everyone to make the most of their limited rations and ‘Make Do and Mend’, which was another successful propaganda campaign.

With victory in 1945 Britain’s infrastructure had either been destroyed or worn out as the only one aim during the six years of war was victory. The country was bankrupt and again there wasn’t any money to resume importing food hence food rationing continued until 1954.

Below are some memories and comments made by local people about rationing:

“We had 14 years of rationing. It finished in 1954, 9 years after the war ended. No one could stock pile food because the food wasn’t there on the shelves. People had to queue in different shops for different items and had to hand in coupons to get their rations. Most people had no fridges. We had a ‘meat safe’ in the cellar, the coolest part of the house. It was a metal box with a grill in the door so the air could circulate. In the early ’50s my Dad cut up squares of newspaper to use as loo roll to save money. My Grandad had an allotment at Broadmeadow and we had lots of home grown fruit and veg. The neighbours had chickens and we got milk from a man who sterilised it in a large pan in his kitchen. We would go to his cottage near Coombe Farm with a quart bottle and fill it up. He took the cream off the top and sold that too. Mum and Gran did lots of home baking. I never felt deprived. It was ‘normal’ the only thing I complained about was the newspaper toilet paper as Dad carried on doing this into the early ’60s.” Barbara Whitton (Facebook Bishopsteignton Banter/Sue Silvester Post).

“Born during the war, I remember the day when sweet rationing eventually finished and I ran all the way to the sweet shop (not in Bishop) with a coin my mother gave me and bought a sherbet dab (Cockney rhyming slang for a cab!)”. Richard Norris (Facebook Bishopsteignton Banter/Sue Silvester Post)

“I lived in Ideford the toilet was at the bottom of the garden, one water tap for the whole street, no electric, walk up to Haldon to pick wood to light the copper for a bath once a week, the men used to go rabbiting at the weekend, kept chickens for eggs, and grew all vegetables, went to the farm with our can for milk, a dolly tub to do the washing with a mangle. I could go on.” Brenda Creber (Facebook Bishopsteignton Banter/Sue Silvester Post)

Present Day ‘Dig for Victory’

As we move into 2020 and over the last 80 years, with recessions and a more awareness from the public with regards to climate change and ‘food miles’, there has been an increased demand for allotments for vegetable growing across the country. Hence ‘Dig for Victory’ Survival is still reverent to this day.

The 25 allotments at Michaels Field were acquired in 2014 offering full or half plots to the residents of Bishopsteignton. There is also a healthy waiting list for those that would like to obtain an allotment to grow their own vegetables while having the opportunity to enjoy an active and healthy lifestyle.

However, the demand for allotments in Bishopsteignton wasn’t always the case, as highlighted in the article ‘No demand for Allotments at Bishopsteignton’ Western Times dated 14 March 1941.

“Mr D Manning of Devon County Agriculture Committee wrote to Bishopsteignton Parish Council that all available land in the parish should be cultivated during the coming season for home cultivation. Replying to questions, the clerk said as far as he knew there was no demand for allotments in the village. The chairman pointed out that there was a lot of ground not under cultivation. It was resolved to reply that there were no applications for allotments.”

Unfortunately, Bishopsteignton Allotments Site is not stated as a statutory allotment site, which is defined as ‘where land is acquired specifically for the purpose of allotments and a change of use requires the approval of the Secretary of State’. The site is leased from Teignbridge Council and its use could change in the future.

But with this in mind the need to have allotments to DIG and GROW produce all year round whether in war or peace times will always be required to reduce importing, reduce food miles and provide a healthy lifestyle for all.

During this VE 75 year a ‘Dig for Victory’ plot will be cultivated as part of the Community Allotment at Michaels Field planted in keeping with the Government Guidelines of 1940. Updates on its progress will be available here.