I still have two physical scars from my time at Bishopsteignton School. One from a burn when I put my arm over the rail that surrounded the ‘tortoise’ coke stove next to Miss Hawkins desk, the stove was for heating the infants classroom; the other is a scar under the chin from being tripped over and travelling several feet along the playground on my chin. With no doctor, available, small accidents were dealt with locally by the grown-ups or if more serious were taken to the chemist.

Most of the mums and grans had many tried and tested remedies handed down over the years. It was too expensive to buy branded preparations when you have many natural ingredients in the food cupboard. One bought item regularly used for cuts, bruises, rashes and grazes was Iodine, it smelled horrible, stung badly and left an orange stain on the skin.

One day a couple of friends and I were walking back from the river through ‘pathfields’. We had been down to the river mainly to stand on the little bridge that crossed the railway and wait for the steam train to come through and get lost in the smoke as it travelled under us. Such simple pleasures.

We would then go down the steep steps to the shore and just wander for a little, picking up shells. We were always mindful of what our parents had taught us. We were to be quiet and respectful to the few men who lived in the tiny dwellings by the river. We had been taught that they were specially retired soldiers who needed to be able to relax in the peace and quiet of the surroundings that the river offered.

On the way back and going into ‘pathfields’, I climbed the hedge instead of using the gate and put my foot straight into a red ants nest. While carrying on up through the field, the pain from the stings and bites was horrendous. Crying and shouting, I was heard by Mrs Burgoyne who lived down the lane at the side of Huntley. She grabbed me and quickly took off my shoes and socks and stuck my feet in a large bucket, she then disappeared indoors and came back carrying a large ‘sweet jar’ of pickled onions and gradually emptied the vinegar and onions over my legs and feet.

Once the jar was empty, she moved my legs up and down and made me sit with my feet in the bucket for 20 minutes. She then patted my legs dry and gently rubbed in a little salt, after a while the pain had gone. Next day there was just some red patches to highlight the drama. My mum took one of her own jars of onions to replace that used by Mrs Burgoyne, but she would have none of it. She told mum she had drained the vinegar down the drain, washed the onions and put them into the jar with fresh vinegar. In the village, there was always someone to help.

When mum had to unexpectedly go into hospital, (she was in for about a week), and everyday mum was away, there was a meal waiting for us when we got home from school and dad from work. People were so kind and we never knew who everyone was that contributed; for example, the chicken pie, the stew or the casserole, the apple pie, the jelly and the apple dumplings. Even the Monday’s washing had been laundered and hung out to dry. Many of the houses, like ours, were never locked so it was easy for people to help without being noticed.

Dad had been a cook in the army and it was mum’s idea that we boys should all learn to cook, launder and iron, and be able to mend clothes and sew on buttons. She wanted us to be able to look after ourselves, as we got older. The winter was a good time for learning, with little else to do except read and listen to the radio. Dad enjoyed his radio but for us kids the only real programme of interest was ‘children’s hour’ and once a week ‘Dick Barton, Special Agent’. We also enjoyed ‘Educating Archie’ Archie Andrews was a ventriloquist’s doll worked by Peter Brough. Honestly, who ever thought of a Ventriloquist on the Radio? However, we loved it.

Dad had his radio, we also had a ‘wind up’ gramophone, (in itself a piece of good polished mahogany furniture) that used 78rpm records and with two doors to open and shut to control the volume. Winter evenings were also the time to bring out the jigsaws, ‘ludo’, ‘snakes and ladders’ and card games such as ‘Pairs’, ‘Happy Families’ and ‘Snap’, The Monopoly and Totopoly was always saved for Christmas.

In the spring, farmer Dawe, whose farm included ‘Old Walls’ would allow village children to pick primroses around the hedgerows in two of his fields. We could go off quite happily without any adults. We had some wool to tie the primroses in bunches and a stick on which to hang bunches upside down to make them easy to carry. We had with us jam sandwiches and a few biscuits or a bit of cake and a small thermos of water. If you were lucky, there was a drop of National Health orange juice added to the water. We would be out all day.

The first bunches of primroses were delivered to the older residents in the village. If we were lucky, we would come across a few violets to pick, which also went to the older ladies in the village. Later on, Mr Baker who owned the woodlands in Happy Valley would allow a few of us to pick bluebells. These were also shared out. It was at these times that we children were taught, in a natural way to respect, care and share with older residents.

Families in each street would support those, where any help was needed. I enjoyed spending time and listening to the memories of the older ones and taking in the words of wisdom that they would share. It was like an extended family.

“It was like an extended family.”

I enjoyed time with (Uncle) Sam Taylor. When I worked on a Saturday at the garage in Fore Street, where I served petrol, paraffin and oddments from the shop as well as waiting for customers to collect their glass accumulators (a type of battery used in some radios), that had been into the garage for charging up overnight. Uncle Sam would call in to see me.

With the workshop closed for the weekend, Mr and Mrs Ward and family, owners of the garage, would go out for the day. During the afternoon, (Uncle) Sam would join me for a cup of tea and a natter; he would then use the vice and hacksaw in the workshop to cut up his twist of tobacco, it being that hard. He would cut up enough to keep his pipe filled for the week. Many years previously, he had owned the garage and had many a tale to tell.

When I left school at fifteen, I went to work for Mr Ward full time at the Central Garage. This was my first step into the big wide world. I only had a weekend off between leaving school and starting work. My starting wage was £2.10s for a 48-hour week, 6 days 9am to 5.30pm, less 30 minutes for lunch. We had the actual bank holiday days plus two weeks annual holiday. This was standard. Mum took her board and lodge money leaving me with £1 a week for shoes, clothes and any social or personal activities. I was also expected to save.

Mrs Ward was a lay preacher for the Methodist Church. They were a super family with Christine and Diane. Their son Patrick was born while they lived in Bishopstgeignton. Mr and Mrs Pugh of Rose Cottage and I were invited to become Godparents to their son Patrick. He was christened at the Methodist Church in Fore Street. The family later moved to North Devon where I visited them a couple of times on my old James 98 motorcycle. Late 1960 or early 1970 they emigrated to Australia, after which we lost touch. I continued at the garage for a short while with the new owners, Mr and Mrs Codling who had moved back to England from Bulawayo.

Mr Pugh had a workshop in the first cottage on Clanage Street. We could sometimes stand by the door and watch him with his machines turning out the finest and most delicate parts for clocks, watches and speciality steel springs and cogs. Mr Pugh also built a miniature railway with engine and carriages. One could ride on it at weekends when he was driving it at Penn Inn pleasure park, Newton Abbot. In the early sixties, Mr Pugh had one of the first-round bubble cars. He later had a Messerschmidt which was longer.

I also enjoyed the opportunity to spend time with (Grandad) Skinner, (Sheila Robbin’s dad). Very occasionally, Sheila and husband Dave would go out and I would keep Grandad company. He was always interested in what I had been doing through the week and how I was getting on at school or at work. He would impart bits of advice, much of which remained with me.

I can remember him telling me to plan my future but do not get too dis-heartened if sometimes things don’t always go to plan, “side stepping” he said “was an important part of learning”.

He was as close as I ever got to a real family Grandad.

Colin’s reminiscences are continued in 6 more parts, visit Born and Raised in Bishopsteignton to read more.

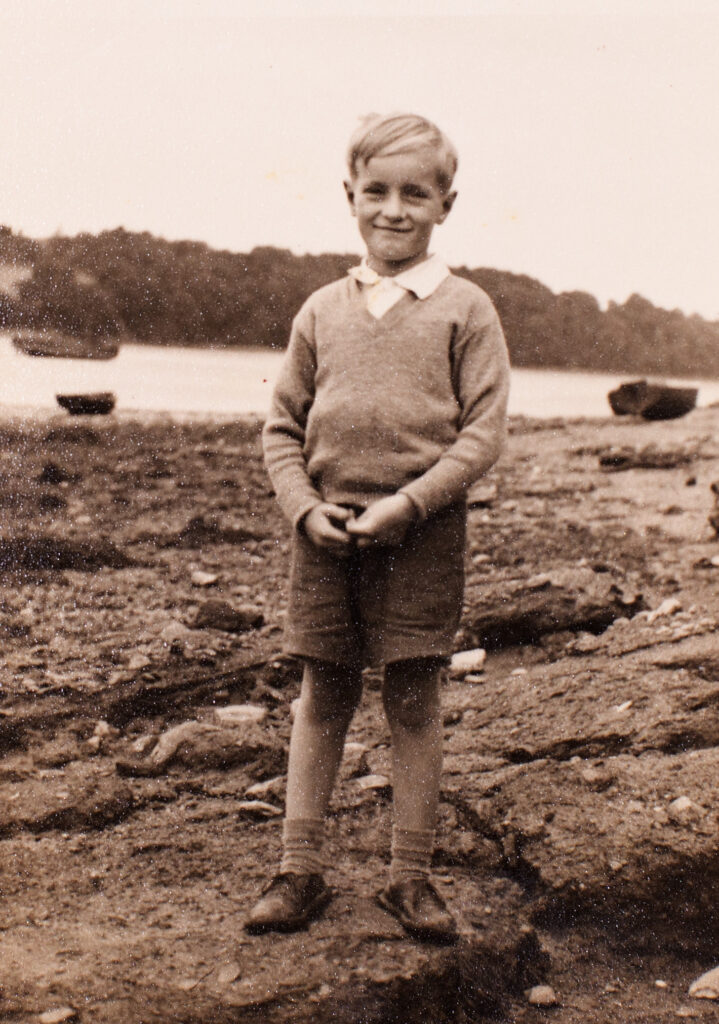

Thank you to Colin Back for his stories and to him and Rowena Bradnam for the images.

This article was assembled by Dawn Rogers and the Bishopsteignton Heritage Hub team.

I still have two physical scars from my time at Bishopsteignton School. One from a burn when I put my arm over the rail that surrounded the ‘tortoise’ coke stove next to Miss Hawkins desk, the stove was for heating the infants classroom; the other is a scar under the chin from being tripped over and travelling several feet along the playground on my chin. With no doctor, available, small accidents were dealt with locally by the grown-ups or if more serious were taken to the chemist.

Most of the mums and grans had many tried and tested remedies handed down over the years. It was too expensive to buy branded preparations when you have many natural ingredients in the food cupboard. One bought item regularly used for cuts, bruises, rashes and grazes was Iodine, it smelled horrible, stung badly and left an orange stain on the skin.

One day a couple of friends and I were walking back from the river through ‘pathfields’. We had been down to the river mainly to stand on the little bridge that crossed the railway and wait for the steam train to come through and get lost in the smoke as it travelled under us. Such simple pleasures.

We would then go down the steep steps to the shore and just wander for a little, picking up shells. We were always mindful of what our parents had taught us. We were to be quiet and respectful to the few men who lived in the tiny dwellings by the river. We had been taught that they were specially retired soldiers who needed to be able to relax in the peace and quiet of the surroundings that the river offered.

On the way back and going into ‘pathfields’, I climbed the hedge instead of using the gate and put my foot straight into a red ants nest. While carrying on up through the field, the pain from the stings and bites was horrendous. Crying and shouting, I was heard by Mrs Burgoyne who lived down the lane at the side of Huntley. She grabbed me and quickly took off my shoes and socks and stuck my feet in a large bucket, she then disappeared indoors and came back carrying a large ‘sweet jar’ of pickled onions and gradually emptied the vinegar and onions over my legs and feet.

Once the jar was empty, she moved my legs up and down and made me sit with my feet in the bucket for 20 minutes. She then patted my legs dry and gently rubbed in a little salt, after a while the pain had gone. Next day there was just some red patches to highlight the drama. My mum took one of her own jars of onions to replace that used by Mrs Burgoyne, but she would have none of it. She told mum she had drained the vinegar down the drain, washed the onions and put them into the jar with fresh vinegar. In the village, there was always someone to help.

When mum had to unexpectedly go into hospital, (she was in for about a week), and everyday mum was away, there was a meal waiting for us when we got home from school and dad from work. People were so kind and we never knew who everyone was that contributed; for example, the chicken pie, the stew or the casserole, the apple pie, the jelly and the apple dumplings. Even the Monday’s washing had been laundered and hung out to dry. Many of the houses, like ours, were never locked so it was easy for people to help without being noticed.

Dad had been a cook in the army and it was mum’s idea that we boys should all learn to cook, launder and iron, and be able to mend clothes and sew on buttons. She wanted us to be able to look after ourselves, as we got older. The winter was a good time for learning, with little else to do except read and listen to the radio. Dad enjoyed his radio but for us kids the only real programme of interest was ‘children’s hour’ and once a week ‘Dick Barton, Special Agent’. We also enjoyed ‘Educating Archie’ Archie Andrews was a ventriloquist’s doll worked by Peter Brough. Honestly, who ever thought of a Ventriloquist on the Radio? However, we loved it.

Dad had his radio, we also had a ‘wind up’ gramophone, (in itself a piece of good polished mahogany furniture) that used 78rpm records and with two doors to open and shut to control the volume. Winter evenings were also the time to bring out the jigsaws, ‘ludo’, ‘snakes and ladders’ and card games such as ‘Pairs’, ‘Happy Families’ and ‘Snap’, The Monopoly and Totopoly was always saved for Christmas.

In the spring, farmer Dawe, whose farm included ‘Old Walls’ would allow village children to pick primroses around the hedgerows in two of his fields. We could go off quite happily without any adults. We had some wool to tie the primroses in bunches and a stick on which to hang bunches upside down to make them easy to carry. We had with us jam sandwiches and a few biscuits or a bit of cake and a small thermos of water. If you were lucky, there was a drop of National Health orange juice added to the water. We would be out all day.

The first bunches of primroses were delivered to the older residents in the village. If we were lucky, we would come across a few violets to pick, which also went to the older ladies in the village. Later on, Mr Baker who owned the woodlands in Happy Valley would allow a few of us to pick bluebells. These were also shared out. It was at these times that we children were taught, in a natural way to respect, care and share with older residents.

Families in each street would support those, where any help was needed. I enjoyed spending time and listening to the memories of the older ones and taking in the words of wisdom that they would share. It was like an extended family.

“It was like an extended family.”

I enjoyed time with (Uncle) Sam Taylor. When I worked on a Saturday at the garage in Fore Street, where I served petrol, paraffin and oddments from the shop as well as waiting for customers to collect their glass accumulators (a type of battery used in some radios), that had been into the garage for charging up overnight. Uncle Sam would call in to see me.

With the workshop closed for the weekend, Mr and Mrs Ward and family, owners of the garage, would go out for the day. During the afternoon, (Uncle) Sam would join me for a cup of tea and a natter; he would then use the vice and hacksaw in the workshop to cut up his twist of tobacco, it being that hard. He would cut up enough to keep his pipe filled for the week. Many years previously, he had owned the garage and had many a tale to tell.

When I left school at fifteen, I went to work for Mr Ward full time at the Central Garage. This was my first step into the big wide world. I only had a weekend off between leaving school and starting work. My starting wage was £2.10s for a 48-hour week, 6 days 9am to 5.30pm, less 30 minutes for lunch. We had the actual bank holiday days plus two weeks annual holiday. This was standard. Mum took her board and lodge money leaving me with £1 a week for shoes, clothes and any social or personal activities. I was also expected to save.

Mrs Ward was a lay preacher for the Methodist Church. They were a super family with Christine and Diane. Their son Patrick was born while they lived in Bishopstgeignton. Mr and Mrs Pugh of Rose Cottage and I were invited to become Godparents to their son Patrick. He was christened at the Methodist Church in Fore Street. The family later moved to North Devon where I visited them a couple of times on my old James 98 motorcycle. Late 1960 or early 1970 they emigrated to Australia, after which we lost touch. I continued at the garage for a short while with the new owners, Mr and Mrs Codling who had moved back to England from Bulawayo.

Mr Pugh had a workshop in the first cottage on Clanage Street. We could sometimes stand by the door and watch him with his machines turning out the finest and most delicate parts for clocks, watches and speciality steel springs and cogs. Mr Pugh also built a miniature railway with engine and carriages. One could ride on it at weekends when he was driving it at Penn Inn pleasure park, Newton Abbot. In the early sixties, Mr Pugh had one of the first-round bubble cars. He later had a Messerschmidt which was longer.

I also enjoyed the opportunity to spend time with (Grandad) Skinner, (Sheila Robbin’s dad). Very occasionally, Sheila and husband Dave would go out and I would keep Grandad company. He was always interested in what I had been doing through the week and how I was getting on at school or at work. He would impart bits of advice, much of which remained with me.

I can remember him telling me to plan my future but do not get too dis-heartened if sometimes things don’t always go to plan, “side stepping” he said “was an important part of learning”.

He was as close as I ever got to a real family Grandad.

Colin’s reminiscences are continued in 6 more parts, visit Born and Raised in Bishopsteignton to read more.

Thank you to Colin Back for his stories and to him and Rowena Bradnam for the images.

This article was assembled by Dawn Rogers and the Bishopsteignton Heritage Hub team.