Ken Dawe

Frank Newton and old Frank Battershall were basically horse drivers. I think Ned Callard was just a general farm worker, to be honest, and there were others, but these are the main characters. Now Frank Newton, horse driver, you could always tell him because he had a red spotted handkerchief round his neck and, of course, when they weren’t working the fields, they had to cut the hedges with a paring hook and late cousin Douglas always used to say that if you wanted to know where Ned Callard was look for a wisp of smoke going up because he always had a fire going. But those were the three I remember. Old Frank was a ploughman and whatever horses they had to use, he did and so was Frank Newton.

Now, from what I can gather, when the war ended – it’s all mixed up a bit, because when the horses had done their working day in the summer they were groomed off down here in Debbie and Stuart’s kitchen and they had to walk them all the way up Walls Hill to the top field against the road below the golf course. That was their summer field and then of course next day they had to walk up, because there was no other means. They had to walk up and fetch them down to groom them up and get them harnessed.

There was one guy, and it wasn’t either of those two because they lived just down the road, but there was another guy they had that used to drive horses. I think he was up from Luton or somewhere. I don’t know how long he worked for Grandfather but he used to walk from Luton to here, probably picked up the horses on his way down, took them down the farm, got them ready for the day’s work, walked behind the plough or whatever it was (because there weren’t very many implements with seating on) all day long, groom the horses off at the end of the day, take them back up the field, walk all the way back to Luton. Now, because he didn’t like the pub up there – or whether he had been barred from it, I don’t know – he would then walk into Teignmouth to a pub and all the way back again. Can you imagine that? But they were as fit as fleas.

Some of it is on this video, the equipment they had was pretty primitive. Old Frank used to plough, now single furrow, they do about an acre a day, whereas when I was ploughing I had a three furrow reversible plough which wasn’t big by modern day standards but I could do an acre an hour. He had what we call a balance plough, now it was the forerunner of the reversible flat plough that turns over so that you are turning the ground the same way whether you are going this way or that, but it was different. One furrow was up in the air and it was pivoted so when he got to the other end and turned the horses, he could flip the thing over and then come back down turning the ground the same way because it was left and right hand furrows.

So, that’s on that bit of film but there’s all sorts of stuff. The self-binders that they used to produce the sheaves. Horses, to start with, used to have to pull those out of a team. They would probably have two horses pulling them down the hill and if there was any uphill work, they would have to hitch on another one or two. Old Frank always used to tell me it was terrible work for the horses, especially on this farm being so steep. If the cutter bar of the binder choked the poor horses have to struggle and try and back it up the hill to clear it but they took it in their stride and of course the seed drills, the hay-making equipment, all the grass was cut by horse-pulled mower and hay turners and horse sweeps because it was all loose hay.

There were no bales in those days. They used to sweep – a big wooden thing with handles at the back that the horse driver used to hold and it had wooden tines out with metal points so they didn’t wear too much and they would break up this hay after the horses had raked it into rows to the rick, and then the chap at the back had to struggle and lift the handles up so the points stuck in the ground and it turned over and left the … It’s all on that film, have you not seen it?… turned over and left the big mound of hay there and then it would right itself and they would go back again.

But then, of course, they were all hayricks. There were no balers in those days. First of all they had a grab, which was a big pole they used to put up with an arm out which was anchored with guide ropes and then they had a rope up around the pulley and they used a grab. Where the heap of hay was deposited, they would lower this grab down and they would push the tines into it – again, sort of manually – and the horse had to pull the rope to lift this up with a great wollage (?) of hay on the back. They would then swing the arm around and drop it onto the hayrick which of course then had to be forked around by hand to make the rick, and the same when they cut corn.

Hayricks

I think old Frank used to tell me that he never did any scything of corn except for around the outside of the field. When they went to a new field to cut the corn, Grandfather didn’t like (because they had a tractor then to pull the self-binder instead of a horse) going round the first round squashing the corn down, because the thing cuts on one side but Uncle Bill, when he took over running it, he used to do that and then go round the other way, and they would cut most of it, but it was all sheaves laid out on the floor from the thing and everybody – I’ve done this – we had to go round (because we had certain steep bits that we still had to cut with a binder even when we had a combine because they didn’t like taking a combine on the steep in those days) and you had to make the stooks.

They used to cut the corn not quite ripe, because if it was dead ripe you would knock out a lot of the grain and it would be wasted on the floor so they used to cut it not quite ripe, it would ripen in the stooks and you had to pick up these things, carry one under each arm and go and put two down like so, and then another two and another two and maybe one at each end depending on the size of the crop however long you made them, and that was done as a matter of course. Then when it was time to gather it, it all had to be loaded with pitchfork onto the trailer which, in my day, was pulled by early tractors and a rick was made.

Now the ricks had to be made properly. They used to put bedding on the floor – faggots of wood – to keep it up off the damp ground which always attracted the rats and they would build the straw rick so that it got wider and wider and wider all the way around and some were rectangular. I can’t remember any round ones but they were rectangular so that the water wouldn’t run down the side of the rick and then they would build the roof up and old Frank Battershall but it wasn’t what I would call proper thatching like you do when you lay it on like so, it was more or less laid on but it did keep it waterproof and I can picture him now in one of the old barns over there cutting spars to thatch his ricks with.

And then of course at some point they had to thresh it out. So originally Grandfather, he bought a threshing machine, but the steam engine used to come in to power it and there’s film of that happening on this farm video. Latterly Grandfather put up a big barn. One of the original barns over there, he put up a big barn because once they opened a rick up they had to keep it dry and that meant they would have to put the thatch back or sheet it down so once they had done whatever they wanted to do of it they would then load the rest up and take it in the barn so it was all under cover and they would bring the thresher there and do it there.

Yvonne: It would be great if we could get the video and sync it up with you telling the story, because you would have all the visuals as well.

Ken Dawe: That went on for quite some while. I mean hay, like I said, in early days was still loose and they used to have to cut it out with a hay knife. Again, the roof was thatched to keep it dry and they would take so much back and they had this long… (I think there’s one up in the shed you might want). It’s a thing about this long, about this wide, with a point, with a very sharp edge with a couple of handles

Yvonne: We’ve got a lot of old farm equipment in the museum, you know.

Ken Dawe: They have to cut it down through then load that and take it back to the barn. Chuck it up in the barn and then feed it down into the hay racks

Yvonne: We’ve got quite a lot of implements on the walls upstairs

Ken Dawe: So have I, because the farmhouse where Rhoda is was covered in that sort of thing, and it’s all up in the shed there.

And then the first thing they did to improve matters, they got a stationary baler which was parked up. A big Fisher Humphries one I think it was – again, driven by a tractor and a long belt – and we had a more modern tractor hay sweep and the hay was in rows as it was turned and he would sweep up the hay and then take it down to where this big baler was, and it had to be chucked up from the ground on to the top of the baler and that would go through and you had the big thing feeding it down and the big ramp squeezing it up. It made ever such big heavy bales and originally they had wire on them but they changed that over to cord, and that’s how it was done, and then of course along comes the pick-up baler towed behind a tractor and then now it’s all round bales.

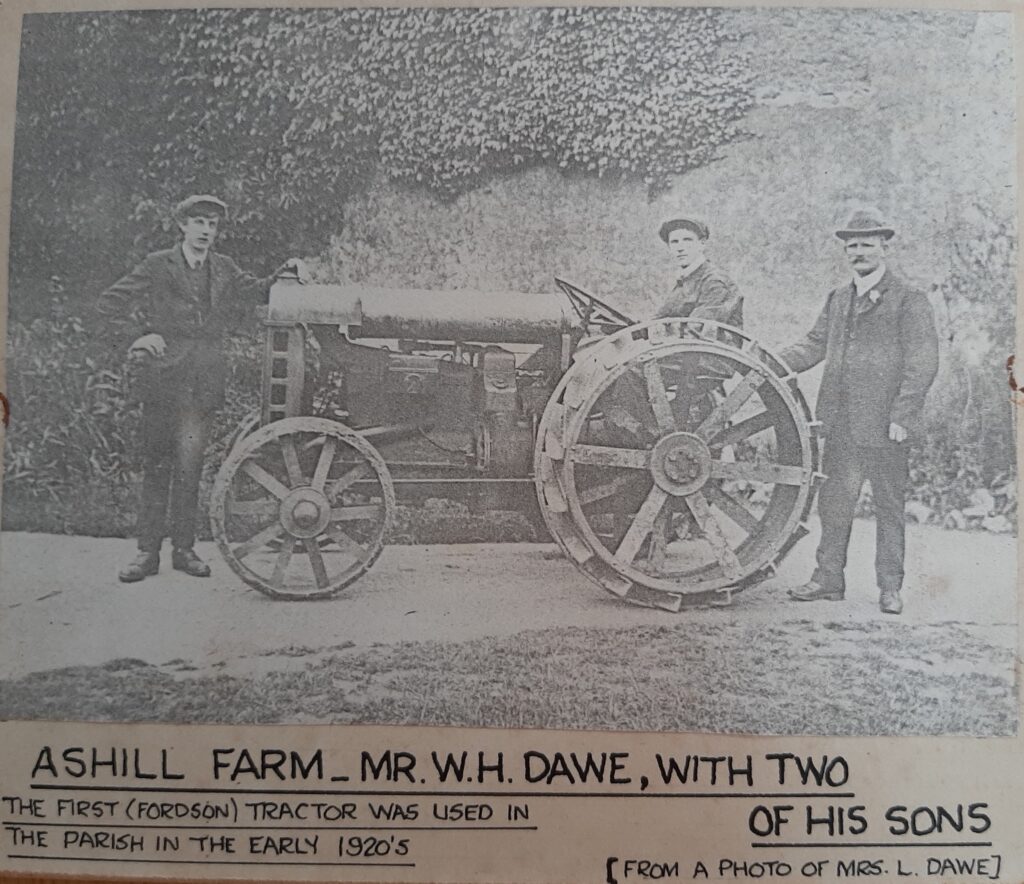

There’s film of Grandfather riding on the self-binder, as they called it, which produced the sheaves, pulled by his eldest son with an old early Fordson tractor with metal wheels and that’s how they did it. Then, of course, in later life since I was on the farm, they’ve had an early towed by a tractor combine but it was a bagger. The corn was all put in two hundredweight sacks in those days and then they would be slid down onto a trailer and we would have to take them back to the farm and stack them. In those days two hundredweight was the norm and they latterly changed it to three bushels which was a hundredweight and a half and now I don’t think they are allowed to lift that sort of weight.

The Dawes with their Fordson Tractor

We used to lug around two hundredweight sacks. You used to put them on your back, carry them up the loft steps and tip them in the bins up there. You wouldn’t believe what we had to do. Then they changed that to a self-propelled combine and they had an early one and then a later one and then when that went we got a bit more modern and had the yellow what was a Clayson combine in those days which has now developed into New Holland. Roger’s got a New Holland combine – a super duper thing – even since I left the farm. But it’s all we had, there wasn’t anything different to do.

Other crops that we used to grow… it was a 600 acre farm because Grandfather came to Ashill which was 240 acres which was like the basis of it and then he bought – call it what you will – Manor Farm or Radway Farm up over that way – that was another 200 and then in the early fifties the brothers bought Coombe Farm which was another 200 odd acres so that made 640 acres

Yvonne: That’s over the back, Coombe way, that area

Ken Dawe: Well, this way, towards Teignmouth. Go up to Headway Cross. Their land started – they bought it off the Sopers, I don’t know if you have come across them; they farmed up Coombe Valley, Teignmouth Coombe Valley – and it went down the other side and right up to Exeter Road. A lot of it was grass because of the nature of the field. We used to have probably about 180 acres of cereals – barley, wheat and oats. Oats for stock feed, barley and wheat were sold off as a grain crop.

We used to grow kale which is like cabbagey stuff for the cows to eat whether be beef or dairy. We had sheep at the time. We probably had about 200 breeding ewes and we used to grow four rows of kale and four rows of swedes all across the field so they could graze that during the winter but the bulk of it was down to grass because that’s the nature of it. We used to bale in the early days, the small bales, we probably did about 200 – 250 thousand hay and the straw was used as well for either bedding or stock feed, probably 100 thousand.

Growing crops on the edge of the Teign

It was a lot but then of course we started making silage for the dairy cows and that was made in a pit where we had a forage harvester that cut the grass standing and it was carted over to Old Walls where the silage pit still is and was filled. This was nothing new. They’ve been making silage for centuries really, but it was put in layer upon layer and we used to put an additive with it to make it ferment right and keep it rolled down with the heaviest tractor we could find and that would preserve fodder for the cows and again, initially, we had to cut that out with a thing that looked like a hay knife but it was a bit better than that, and then we got a grab that went on the front of the tractor.

They always used to come from over there back to here to start with, to the dairy here, but in the early seventies we scrapped that and we had a new dairy unit down just below where Roger’s house is now, a big place there for 100 milking cows and, of course, silage was taken down there; still loose, we had to load it in a trailer and then Max would fork it to the [???] because the cows, in the winter, never went out at all. There were stalls, or cubicles, for 100 cows. It was quite modern at the time. We had a six by six herringbone parlour – that’s six one side staggered, and six the other. Bulk milk tanker, of course. The tanker used to come at seven o’clock in the morning to pick the milk up and cake hoppers above. It was all quite civilised then. Not that milking was my forte but we had to do relief milking because Max and the people that came after him couldn’t work seven days a week. You’ve heard of Brian Nicholson, have you?

Yvonne: I don’t think so

Ken Dawe: He was my buddy. He started farming when I did and he lived down Coombe Way. Do you know Kate and Wally? – he’s the window cleaner. The first cottage on the left as you go down, that was owned by a chap called Webber going back a long way, but the next one Brian lived in and the next one again – they adjoined – was where old Frank used to live.

Withy Cottage, where Mr Webber lived

Brian and I used to do the relief milking but especially in the summer, when the cows were out in the field we would be getting them in probably a quarter to five in the morning because we had to get it done for seven o’clock for the milk lorry to pick up. Once we had done all the milking and cleared up, Brian had to come back up this end to deal with all his young calves that he was rearing and I had to get on and feed up everything over the way so it was a long stint when you were relief milking and of course it all started again four o’clock in the afternoon

Yvonne: Hard life, hey?

Ken Dawe: Didn’t think nothing of it, to be truthful.

When Grandfather came there were no buildings like there is now, just cow byres if you like, which he knocked most of them down and put up the brick buildings that are there now. They had South Devon cows to start with, which were normally classed as a dual purpose animal because they would provide milk with a fairly high butterfat and they were also good for beef as well, so of course all the bull calves went for beef and then the replacements for the dairy – obviously heifer calves – were kept from females. Then we swapped over to Ayrshires – you’ve heard of Ayrshire cattle? – because again they gave more milk and we had to have the whole herd de-horned once because they were a bit – not to people but to themselves.

Yvonne: Are they the ones that have the big horns?

Ken Dawe: Yes, fairly. It was the thing to do then to have their horns sawed off. The vet obviously did it and they used to deaden it, of course, but they looked a bit sick for a few days, and then we gradually switched over to Friesians. As soon as I left the farm – the late 80s – Roger got rid of all the cows. He wasn’t going to be doing milking. He got rid of all the milking equipment, the whole lot and I think that’s more or less what’s happened to most of the farms in the local area. Apart from one big farm up in Luton way – dairy – I don’t think there’s any dairy herds around now, which is a shame because that’s all you used to see in the past was milking cows.

So that’s that. I haven’t finished yet! Well, other crops we used to grow of course were mangles – have you heard of mangles? We used to grow about 20 acres of them for stock feed in the winter. Absolutely useless as a feed because they are ninety per cent water but the beef bullocks and the cows used to eat them. Again, all done by hand. The kale that we used to grow, and the mangles all had to be hoed when the plants came up because we never had in those early days what they now call rubbed seed because the seeds are in a cluster with three, four, five seeds and of course you put it in the ground and you get four, five, six shoots coming up. Well you had to single them to one and gap them to nine inches apart so the hoes were nine inches so you used the point and put the edge of the hoe on the ones you didn’t want and push them to break them off and then you would gap them.

We had to hoe about twenty acres of this stuff, and mangles, but then they gradually brought in what they called rubbed seed which was just a single seed, which then all you had to do was gap them. We used to have a steerage hoe which one of the old hands from down Coombe Farm on his little Fergie used to do but you had to have somebody behind on a seat. It had a seat and that would get rid of the weeds between the rows. It’s all a bit primitive by today’s standards, but that’s how it was. We had, of course, probably 200 breeding ewes.

Everything was hand milked in Granfer’s day, obviously, and then they gradually got machine milked. In fact, when he had the new complex where what was now called the dairy, that was the milking parlour, and they could milk probably six at one go so they would come across from the shippen which was just across the yard into the parlour. They would be milked and they could go out the other door, and they would go into a collecting yard until the job was done and then in the summer they were walked down to the field for eating the grass and I think that’s why, where the Vickery’s house is now, there’s a big covered yard and I think that was put up for them.

We tried to get more cows in the shippens in the winter than what it would hold so I think we had the covered yard to use because cows out in the winter, they just make such a muck of the land, and they were fed accordingly of course. That all had to be done. Hand milking first and then after the milking parlour they fixed up what we call round the shippen milking where there was a pipeline all the way round the shippens and first of all you had your buckets which were vacuum controlled to actually milk the cows with the cluster that goes on to the udder and then if you turned taps up on these pipelines it would suck the milk out of the churn and it went down the pipeline into the little dairy.

Milk had to be cooled, of course. We had in-line coolers and churn coolers because it was still collected in churns in those days. You know I keep telling you that down the bottom there was the old churn stand. We had to, with a trolley thing, get them down there and lug them up on the top. That’s where the lorry used to pick up and then we built – I suppose it’s still there – a churn stand just up from Vickery’s garage or shed. Is it still there? I suppose it is, and we used to have to pull the churns up there.

Yvonne: They used to deliver churns round the village. There was a horse and cart, wasn’t there.

Ken Dawe: My father and Uncle Ern used to do the milk round, so they would do the milking, cool the milk because a lot of it was bottled in those days, and they would load up, initially, pony carts, and latterly vans, and they supplied milk to all the village, and Teignmouth, and people didn’t want bottled, they would dip it out with a dipper and fill their jugs up.

G Wills pony & trap milk delivery

Yvonne: It’s David Quantick that can remember them coming round with the milk [1] & [2]

Ken Dawe: In fact, one winter – this is a long time after we had gone bulk – we had snow and the lorry couldn’t get here and we had the bulk tank which probably held about four or five hundred gallon was full and cows had to be milked so we had what we called a temporary tank. It was like a plastic bag, probably as long as this table and about that wide and we filled that and when that was full we didn’t know what to do so – we shouldn’t have done it really because it was unpasteurised but I went round the village giving it away

Yvonne: How did you get round the village if it was all under snow?

Ken Dawe: Well, tractors – it was alright, but we shouldn’t have done it really because it wasn’t pasteurised.

Yvonne: Well, it hadn’t been pasteurised for many hundreds of years before that.

Ken Dawe: No. In fact, I was raised on untreated milk and when I married Lesley and I still used to go down and fetch it, it made her ill but I had been raised on it.

We used to have bulls in the early days to service the cows but eventually that was succeeded by A.I., artificial insemination. You would ring up – the place was down at Dartington – because then you could choose which bulls you wanted for any particular cow, rather than one you had in the bull pen. You would just ring up, keep the cow in and the job was done. So that made sure you could get top quality bulls for better cows and produce better calves.