Notes on research methods and sources from a paper given by Ian Roberts.

The ‘R’ word. Mention it in polite company and people glaze over or move on muttering ‘that’s not for me’, ‘a bit geeky’, ‘I’m not very educated’ and so on. The truth is that anyone can research providing they have an interest in what they are researching, can make good judgements, are inquisitive or simply just plain nosey! So whether it’s ghosts and folklore, big houses, farming, genealogy or pubs or whatever:- if it tickles your fancy start researching it.

Research is often a bit like a detective story. We know something has happened and now we are going to collect facts that will develop the story and explain what led up to it and what its implications were. Or we may have a theory about something and want to find facts that will throw more light on it and justify or refute it. For example some people say Coombe Vale was always called that others say it was named after Philip Coombe who built the newer houses in it. How would you go about solving this question?

Whatever interests you, you will need to be systematic and enquiring about your approach.

You will need to first collect data or the facts about your search. These may be objects, printed or written records, materials and statistics, or recorded conversations and images. Just think about these and sketch out the different forms these all can take. Any information is data, the trick is to make sense of it.

Where your facts come from varies hugely and will differ according to your topic but here is a summary.

• Google and search engines including specialised ones such as Libraries and County Archives

• Newspapers (for a tiny village like ours local papers are most likely to shed light)

• Books

• Academic journals and text books

• Official Records ( County Archives, Museums, Genealogy sites)

• Official statistics (census, mortality bills, trade statistics)

• Archaeological evidence

• Photographs, film and pictures

• Observation

• Oral accounts, very important because most events are not recorded especially about ordinary life and people

These can seem daunting but there are many people in BH who know a lot about sources so why not discuss your topic with them or put it up on Facebook and see what comes up. BH also has access to some closed sources of information such as newspaper archives, the census and migration files.

We hear a lot about false news, well even true facts are subject to distortion and inaccuracy. As Hunter Thompson once said the only true fact is the sports score. So the good researcher is always skeptical and critical of the facts he or she collects.

Let’s run a quality check to see if the facts are true.

• Reliable – can you trust the source? By and large one might be skeptical of a fact on Facebook or in a red top paper; hardly skeptical about National Office of Statistics information that has rigorous standards.

• Is it complete?

• Valid – is it true does it make sense?

• Consistent with other evidence?

• Is it accurate – does it give accurate detail for us to make sense of?

• Is it biased, does the source have an axe to grind and are you blind because you want the fact to be true?

By and large no one fact alone solves the research question and very often a single fact is incomplete to the extent that it cannot be used by itself but rather as a clue. So to get the fuller picture we need to gather several facts often all incomplete until we can make up the jigsaw and see the full picture. Technically this is known as triangulation.

Some people think that research is a lonely business but nothing can be further from the truth as talking about your research with others will bring to your attention facts you did not know as well as different interpretations. One of the great things about BH is that it encourages sharing your information with others either through the web site or by meeting up. Some researchers like to work all the time in partnership with others.

The story is still not over because when we collect the facts we need to interpret them otherwise we are doing no more than ‘stamp collecting’. What we are trying to do primarily is to discover what happened and secondly, and perhaps more difficult, to explain and interpret it, especially as the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

Rudyard Kipling wrote about six honest serving men which, to him, were the basics of being a journalist and equally so a researcher.

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

I send them over land and sea,

I send them east and west

But after they have worked for me,

I give them all a rest.

In front of these put the words ‘I wonder’

Did you say to yourself about the poem above ‘I wonder what it is called’ or better still ‘I wonder where I can find out the name of the poem’? And even more impressive did you read a little about the context and meaning of the poem? If you did all this then – you’ll be a researcher my son!

Let’s briefly look at a case study.

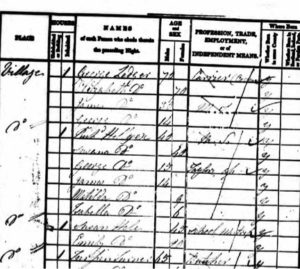

I am looking at the 1841 census.

Despite being a census it was the first one and largely untested and using enumerators barely trained and of varying literacy.

1841 census information Hellyer family Bishopsteignton

While we are sure this record is authentic you can also see from this copy the census is vague in not giving street names or house numbers. It is also incomplete because it seems to ignore Radway (is there another book to find as we do not have the whole picture for Bishopsteignton?) Neither do we know which houses existed then. But we can bring more accuracy by triangulating this with households nearby who had servants which are thus likely to be bigger houses, and further so by seeing if the Head of the household is mentioned by name and house name in other records.

We can also see that the records are frustratingly abbreviated and illegible at times. Finding other source such as Census Abbreviations that can help can increase some accuracy. Help is at hand though inasmuch as there is modern typed transcriptions attached at the bottom, but as a researcher be ever skeptical as these are sometimes wrong so make sure you use the evidence of your own eyes!

So far we have done little more than stamp collect simply knowing the names, occupation, age and gender of people living in the village at unspecified addresses.

Time to start triangulating. In the museum collection is a lovely sampler embroidered by Matilda Louise Hellyer aged 8 in 1840. The researcher then asked me if I could locate such a person. Can you? Look carefully above.

We find her probably somewhere in Fore Street living with her family and with a father whose occupation is illegible. However another researcher has found another document saying he was a postman. Maybe, but what I see in the census looks nothing like that so we need to look at both records and judge their accuracy and validity. Don’t go for a fact just because it seems to fit the jigsaw.

One question that arises is that we know the top end of Fore Street was called Post Office Street then. Might it be the family lived in the post office? Might it be that postman was synonymous with post-master? This is creative speculation that is important in driving your research but don’t make an assumptions about it until you have gathered more evidence otherwise you may be making fake news!

If you see the sampler you will be impressed by the quality of work for an eight year old especially one probably living in a humble abode. If it was like my cottage nearby it was as dark as night so embroidery would have been hard. Two other pieces of evidence jump out of the census. The first is that her brother was a tailor’s apprentice. The second is that the Hellyers crop up elsewhere in the village. Just down the street is a milliner named Ann Helyer age 23 (did you spot the single L which is probably transcription or entry error?). So is this a family with sewing as its trade? If so, it could explain the quality of her work. It might also provide evidence on the trades of the village and the role of women. This census hardly ever records the occupation of women but other sources tell us that women ordinarily did not have occupations but would do piece and casual work as the demand and the seasons required. If so could Matilda’s mother have been a seamstress herself taking in work when she could? Sometimes the present does not seem so far away from the past with the gig economy and zero hours contracts.

Sadly we also know from the death index that Matilda died when she was fourteen. Further research could expand on this and find why she died. This in turn could be followed through into disease and living conditions in the village.

The school records could tell us if she was formally schooled, she was obviously literate. So in this one piece of research we can unearth data concerning social history, women in the village, trades and business, infant mortality and a more three dimensional picture of village life in the 19th century.

HAPPY RESEARCHING, HAPPY STORYTELLING